Asteria Malinzi

Baridi la Ufukweni, 2021

Picha, video na sauti.

(Video Poem was produced in collaboration with Ngollo Mlengeya)

Umekwishaonywa. Mchecheto usiomithilika unaikodolea milele zote zinavyotiririka mithili ya vijito. Umekwishaonywa; kwa wepesi uliojaa hadaa mawimbi yamesheheni historia, yanazisomba ndani ya wimbi liendalo masafa ya mbali ya upotevu na kuzisambaratisha ndani ya sauti ya sahau. Umekwishaonywa; mawanda yasiyo na rihi wala fukuto huinyemelea dunia na ngoma, hatua mbele, hatua nyuma. Umekwishaonywa. Maji hayana budi kuyaandika kwanza mawazo makuu ya mwanga.

You have been warned. Great restlessness watches eternities pass in the flowing manner of streams. You have been warned; with deceptive softness waves carry histories into the distance on tides of loss, and thrash to the sound of forgetting. You have been warned; vastness without scent nor warmth stalks the world in dances of advance and retreat. You have been warned. All the great thoughts of light must first be authored by the water.

Abigail Kiwelu

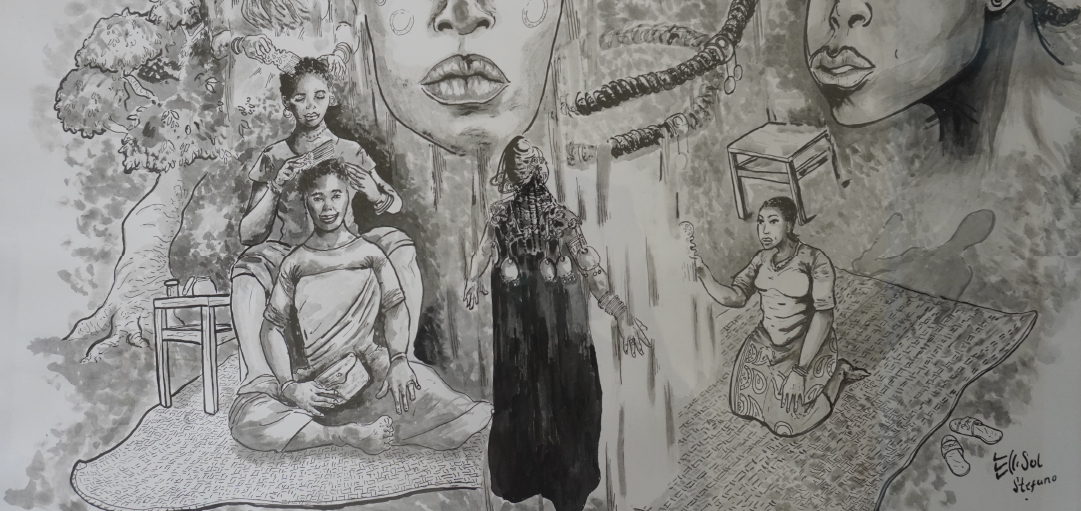

Asu na Maajabu ya Wahenga, 2021

Sehemu ya hadithi iliyo na vielelezo vya Stephano Rafael, sega za mbao, na mkeka.

Usiku unasikiliza kwa makini chumbani ambapo Asu anaendelea kufanya jadi yake. Anaukunjua mkeka, unatoa sauti ya ndege aliye tayari kuruka. Chanuo linamweka mkononi mwake mithili ya nyota. Anapojisogeza hadi katikati ya chumba, Asu anaifumbata nafasi mkononi, ndani ya mkeka mkuukuu akiwa na maswali mengi kichwani. Ndani ya maswali haya anauona utovu mkuu wa fadhili dhidi ya wanawake ambao anajiandaa kuukomesha kwa maneno ya uzima toka kwa Wahenga wake. Anagonga chini chanuo, upepo unaibuka, na mwanga mkali unamulika.

A story excerpt featuring illustrations by Stephano Rafael, wooden combs, and a mat.

The night listens intently in the room Asu forges for her ritual. She unfolds her mat with the ruffle of a bird geared for flight. The comb gleams in her hand with an inward, starry depth. Moving to the center Asu holds space in her palm on a mat made of time with questions on her mind. She sees in these questions sections of a great unkindness borne by womankind which she awaits to break with the life giving words of her ancestors. She taps her comb, the wind rises and a great light appears.

Ngollo Mlengeya

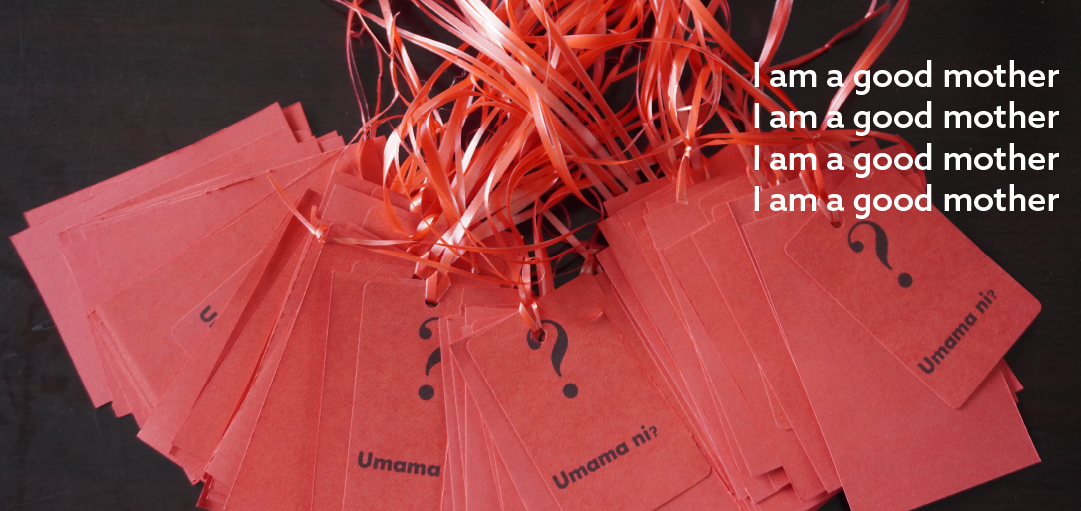

Mimi Mama (I am Mother), 2021

A text installation.

Huu mwangwi wa sauti zinazorindima kwa vizazi vingi duniani kote zinadiriki kupingana na dhana ya kimungu ya Umama. Ni ghani zinazotoka kwa Mama, ‘upeo wa ukamilifu’, zinazosimulia sehemu ya safari yake ya kumiliki utenzi, tukio kwa tukio; tangu kujishuku, kutokuwepo, sonona, na kimya chenye mshindo kinachoambatana na tafsiri ya kubambikizwa ya umama. Hapo ndipo tunatambua kuwa, utambulisho wa kimapokeo ni nanna mojawapo ya kusahau. Lakini hapohapo tunagundua kwamba, tofauti na maadili na Taraji; ndani mwa kila mmoja wetu, furushi lililopambwa na neno hili; limefumbata mbegu iliyopandwa kwenye kumbukumbu, jumuiya, jadi, kujikubali na upendo kama uelewa wa pamoja miongoni mwa wote wanaolikiri neno hili Mama.

These echoes, spanning generations, dare to contend with the universally divine concept of Motherhood. They are incantations, stemming from Mother, an ‘icon of wholeness’, told in segments recounting a journey towards agency through scenes noting the guilt, absences, trauma, tension, and untold silence that accompany a motherhood defined by external factors. Here we understand an imposed self is a form of forgetting. But here also we see that encased in each of us adorned by this word; contrary to the prevailing norms and expectation; is an eternal hum of collective understanding by all who have borne the name, Mother, the seeds of which are planted in memory, community, ritual, self-acceptance and love.

Liberatha Alibalio

The Mender, 2021

Video, photography, sound, and fabric.

(Video Poem was produced in collaboration with Ngollo Mlengeya)

Mirindimo ya mshoni pengine hujidhihirisha kwenye viimbo vya mijadala mikuu ya dunia mbili: kuna biashara. Humo kwa kejeli kidogo, huduma ya mshoni hupata wasaa wa kubezwa na baadaye hukubalika kuwa kielelezo cha mazuri yajayo, kwa muonekano na umiliki. Kisha kuna kazi. Masaa ya kujilea, kupona, kukua na kushiriki, mambo ambayo vilevile hupuuzwa japokuwa yamejikita imara nyakati zote ipozungumziwa dhana ya nyumbani. Katika haya na mengine mengi, kazi ya mshoni husikika katika historia inayomtaka anyamae na hali nyuzi huimba nyimbo za matukio na siri za historia anayoifuma, na kuamsha kumbukumbu ndani ya jadi na kusimika uwepo wake ndani ya safu za historia.

The Mender’s rhythm exists between worlds of which just two perhaps can be articulated in a tone consistent with dominant narratives: There is trade, where with little irony the menders care, occupying time dismissed, comes to be displayed as welcoming face of colorful new worlds to be seen and owned. And there is labour, hours of nurturing, healing, growing, and sharing that are equally dismissed while remaining prevalent in notions of home across existence. In these and many cases the Mender’s work is vocalized by the very history demanding her silence and yet singing in thread, she weaves scenes and secrets, activating memory in ritual and staging her presence in the layers of history.